by Aaron Wirsing

On the 24th of March, while on sabbatical leave, I travelled to Sydney, Australia to begin a six-week research sojourn sponsored by two of my colleagues at the University of Sydney: Thomas Newsome and Chris Dickman. Over the next few weeks, I'll be updating this post with dispatches from down under.

On the 24th of March, while on sabbatical leave, I travelled to Sydney, Australia to begin a six-week research sojourn sponsored by two of my colleagues at the University of Sydney: Thomas Newsome and Chris Dickman. Over the next few weeks, I'll be updating this post with dispatches from down under.

| Shortly after arriving in Sydney, on the 30th of March, we set forth for the Simpson Desert for a week of field research, traveling in two of Australia's iconic field vehicles: Toyota LandCruisers and Hiluxes (pictured). After crossing the Blue Mountains outside of Sydney, and dining on meat pies (another Aussie institution), we found ourselves in open farm country, which in turn gave way to dry rangelands and eventually desert. The emptiness of Australia's interior is truly striking and, for someone like me who spends so much time in the city, something to be cherished. |

| As we passed from New South Wales into Queensland, Tom and I encountered the dingo proof fence, the world's longest fence at approximately 5,500 km! The fence is an attempt to protect sheep by excluding dingoes (Canis dingo) from almost a quarter of the continent, and is a sobering reminder of the dingo's dubious status as a pest here in Australia. A growing number of studies now point to the dingo's role as an important top predator that suppresses herbivory by kangaroos and numbers of smaller, invasive carnivores (red foxes and feral cats), creating a paradox whereby these canids are cast as both villains and ecological heroes (photo by Tom Newsome). |

Overlooking Australia's "Red Center", on the outskirts of the Simpson Desert in western Queensland (taken April 1, 2016).

We reached the Desert Ecology Research Group (DERG) camp, in the Ethabuka Nature Reserve, on the 1st of April, after three grueling days of driving through New South Wales and Queensland. Now in its 26th year(!), Chris Dickman's longitudinal study in the Simpson Desert has become one of the world's signature explorations of the controls on animal behavior and abundance in arid environments. Among many other pursuits, Chris is currently examining whether cover augmentation, in the form of artificial tunnels, might mitigate the impacts of predation by introduced cats and red foxes on native marsupials, including his favorite species the hairy-footed dunnart (Sminthopsis hirtipes).

The Ethabuka campsite, at sunset. Sunsets were a favorite time for me in the Simpson Desert because they set the red sands ablaze.

| Each morning during my weeklong stay in the desert, we began by checking several grids of pitfall traps. Chris Dickman and his colleagues have been using these traps to track fluctuations in the abundance of sensitive small mammals and reptiles in relation to environmental changes such as rainfall and the presence of predators like red foxes. The highlight of these trapping sessions for me was getting to handle and release a mulgara (Dasycercus cristacauda), Australia's 8th largest native mammalian predator. Mulgaras can deliver quite a bite, so I had to stay on my toes while mugging for this photo (by Tom Newsome). |

| The undisputed highlight of my stay in the desert was a near face-to-face with a dingo. Tom and I were searching a watering point for predator scat with a couple of volunteers, when all of a sudden a lone 'black and tan' dingo burst from the brush, not five meters away! I was so startled that I didn't get any pictures, and soon the dingo had disappeared into the bush again, but I'll never forget being so close to Australia's top mammalian carnivore. Later on, I snapped this photo of some reasonably fresh dingo tracks, which as is often the case were following a road (dingoes like to travel efficiently just as we do). |

| My first catch of the day (photo by Eveline Rijksen). | Near the end of my stay in the Simpson, I got the chance to assist with capturing a few military dragons (Ctenophorus isolepis). These small lizards are really quick, so catching them is no small feat. The capture method involves using a monofilament noose at the end of a fishing rod; yep, that's right, lizard fishing! The key is to approach stealthily, so as not to elicit flight, and then to carefully slip the noose over the lizard's head and pull it tight. I snagged three in this manner, but not without a bunch of near misses first. All of the dragons we captured had been equipped with transmitters, for the purpose of tracking their movements in relation to temperature. From my discussions with the graduate student doing the work, Eveline Rijksen, military dragons are good at staying cool despite punishing heat that can exceed 70 degrees C at ground level during the summer. |

On the 7th of April, I said goodbye to the Simpson, but not before taking in more of its savannah-like landscapes and another sunset.

| Back in Sydney, I got the chance to spend a few days as a guest of the Dickmans. Chris and his wife Carol were wonderfully gracious hosts, who among other things took me to Centennial Park to see the resident flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) colony. Flying foxes are fruit eaters, and the members of this huge colony, which numbers in the thousands, make use of the Park's many fig trees. The bats were everywhere and made quite a ruckus. I'm surprised that they aren't more of a tourist attraction, especially given that the Park itself is quite stunning. |

From April 14-16, I had the pleasure of spending a few days in Melbourne (Victoria). Much like the the rivalry between Seattle and Portland for top honors in the Pacific Northwest, Sydney and Melbourne are engaged in an eternal contest for the title of Australia's trendiest city. Both have their charms, with Sydney sporting spectacular scenery and Melbourne a vibrant central business district (CBD). I was there to give an invited talk at Melbourne's Deakin University, where Tom has a postdoc appointment. My talk titled, "Ecological impacts of gray wolf recolonization in managed landscapes of the western USA" was well received. Many thanks to Euan Ritchie and the Centre for Integrative Ecology for hosting!

Melbourne's famous central business district (CBD), along the Yarra River.

Yesterday (April 21), I gave a guest seminar at Sydney's Taronga Zoo, as part of the Youth at the Zoo (YATZ) program. The crowd consisted of about 20 high schoolers, aged 13-19, to whom I lectured about wolves and my wolf-prey research in Eastern Washington. At the same time, Tom Newsome drew parallels to Australia's top canid predator, the dingo. The students ate it up and asked lots of great questions. I hope at least one of them left with renewed appreciation for top predators, and especially for dingoes, whose perception down here definitely needs a makeover.

On ANZAC Day (April 25th), we set forth to the Tanami Desert, where Tom Newsome conducted his dissertation research on dingoes nearly a decade ago. We first flew to Alice Springs, the fabled Australian city with the shortest average distance to coastline, and then drove to the remote town of Yuendumu, one of central Australia's largest indigenous townships. There, we were joined by four members of the Central Land Council, which administers much of the area around Alice Springs on behalf of region's Aboriginal communities. Our goal was to explore dingo diets across the Tanami region by sampling scats, or "gunna". Upon reaching the Desert, we were joined by several more helpers from the local Newmont Mine, at which point the gunna sampling team was complete!

| The legendary 'Tanami Track', a 700+ km stretch from Alice Springs to Halls Creek (WA) that lacks any services and features breathtaking desert vistas. Many adventurous Aussies prepare for years to tackle it. With its many corrugations (washboards) and potholes, I can attest that this road isn't for the timid. | The April 2016 "gunna" sampling team. We spent three long days scouring the Tanami Desert for dingo droppings, ultimately collecting more than 800. Tom will now use these samples as the basis for a diet study. |

The Tanami Desert features the striking contrast of huge, bright red termite mounds, some more than two meters tall, set against meadows of verdantly green spinifex grass. I found the combination to be spellbinding, particularly with the right lighting. Interestingly, termites are the only herbivores that can digest spinifex, which is high in silica.

On our first day of scat sampling (April 27th), we were lucky enough to encounter some dingoes that, presumably because of past reliance on anthropogenic subsidies (garbage), had lost much of their fear of humans. Instead, they allowed us to get close enough for some really great pictures, and one even ran off with a roll of our garbage bags. Here, a resting dingo allowed me to snap a few photos, with no magnification, before running off.

| As a PhD student at the University of Sydney, Tom found that access to human foods in some regions of the Tanami had led dingoes to alter their diets, abandon territoriality, and instead gather in large numbers around subsidized locations. As a first step, we'll use the scats we sampled to test whether the closure of the dumps on which some dingoes in the Tanami used to rely has resulted in more natural foraging patterns. Fortunately, we sampled several areas that were far from any human impacts. These areas will serve as baselines for establishing 'normal' dingo diets that can then be compared to areas where dingoes used to exploit human foods. |

The next day, we sampled Mount Davidson, a remote area of the Desert that is free of human food subsidies and, consequently, where dingoes must make use of wild foods. Our arrival startled three dingoes, which unlike the previous group quickly retreated into the bush. Hence, no pictures, but happy to have spotted truly wild dingoes.

Mount Davidson in the distance. Because of its remote location, the Tanami Desert is home to among the purist dingoes in Australia, with almost no genetic evidence of interbreeding with domestic dogs. Better yet, the dingoes at Mount Davidson exist far from any current human activity and must therefore make a more 'natural' living off of bush tucker.

Our final day of sampling in the Tanami took us to the area surrounding Sangsters Bore, which is of genuine personal and conservation significance. In 1958, Tom's father Alan, a renowned Australian ecologist and expert on dingoes and other denizens of the Red Centre, discovered a remnant population of Mala (rufous hare-wallaby, Lagorchestes hirsutus), which at the time were believed to be extinct. The site of this momentous find was a large sand dune (below, behind me), rare for the region and sporting distinctive vegetation. The reason why Mala held on at this peculiar dune while being wiped out by feral cat and fox predarion elsewhere remains a mystery.

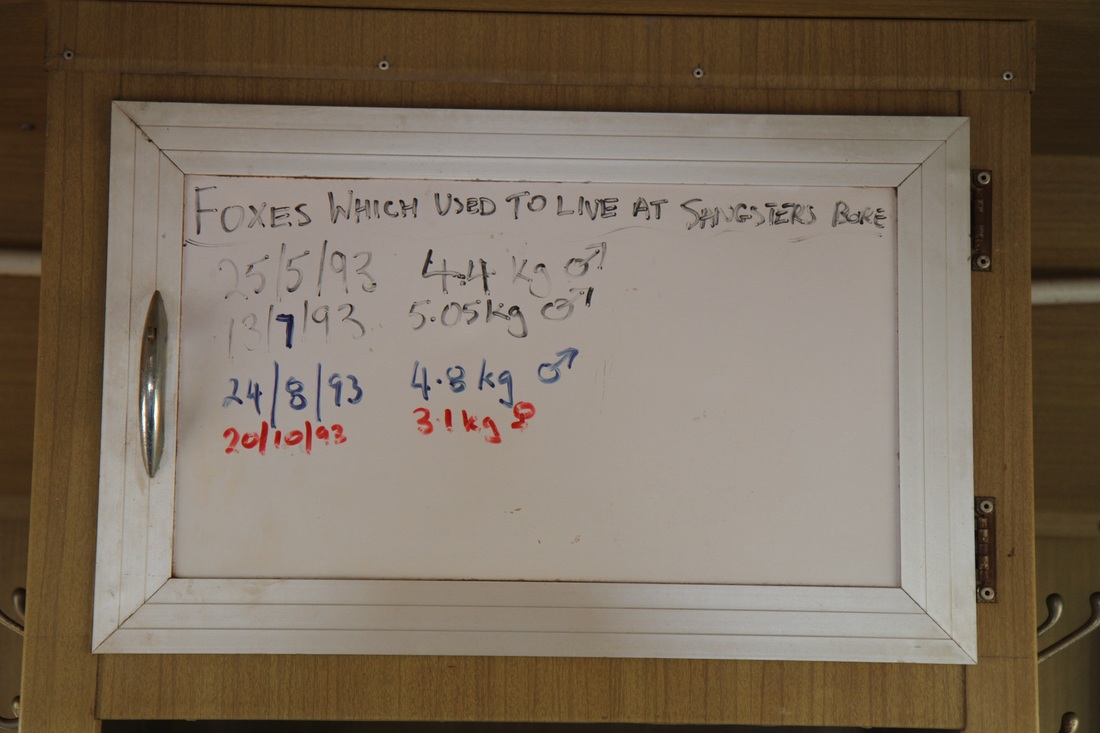

Later, beginning in 1980, other scientists returned to the dune site to initiate a last-ditch Mala rescue operation. Working out of this lonely caravan and surrounded by seemingly endless (albeit enchantingly beautiful) desert, they captured the last few Mala to start a captive breeding effort that continues to this day. Today, no Mala live in the wild on the Australian mainland, though small reintroduced populations do exist on a few offshore islands (e.g., in Shark Bay). All that remains of their memory in the Tanami is contained inside the caravan, in which you can still find a white board tallying the biologists' final efforts to eradicate foxes.

At the conclusion of our Tanami endeavor, we were seen off by another desert sunset.

With my Australian sojourn winding down, I shifted into tourist mode and spent a few days south of Alice Springs visiting iconic Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. On the way, we passed by Mount Connor, a formation so often mistaken for Uluru that it has been dubbed "Fooluru".

Mount Connor is indeed impressive, but it pales in comparison to Uluru. Uluru, or Ayers Rock, is the world's largest "cleanskin" rock and among the oldest rocks in existence. Rising majestically out of surprisingly verdant surroundings, it is utterly mesmerizing. For me, Uluru is among a very small number of places that are truly unique and special. I cannot wait to return, in particular because cloudy weather robbed me of prime sunset and sunrise viewing.

Behold, Uluru! Thank goodness for "panoramic" mode. The hike around its base is 10.6 km, and an absolutely must for all lovers of adventure.

Less appreciated but just as stunning, Kata Tjuta (sometimes called "The Olgas") offers better hiking and one absolutely breathtaking overlook (#2). The cloudy weather may have diminished the area's myriad colors, but neither the rocks' splendor nor my enjoyment.

| The view from the second overlook at Kata Tjuta (right). The hike to its top is challenging, but well worth the effort. Further improving the experience, I had the park virtually to myself. Accordingly, I was able to freely photograph my surroundings and wore out both of my cameras. Haven't gone that crazy since a trip to Glacier NP back in the early 2000s. Kata Tjuta combines brilliant red rocks, green spinifex, and blue skies. It's paradise. |

One the eve of my departure (May 7), I returned to Bondi Beach for one last run along the headlands. Gazing out over the Pacific Ocean at an overlook along the way, I experienced a bittersweet moment, saddened that my unforgettable stay in Australia was coming to a close but also eager to begin the voyage home. Seattle, here I come!

| Coogee Beach (above). A nearby overlook offered some amazing views (to the right, and below). | Don't worry Brooke, I was wearing a protective hat (the Australian sun is notoriously brutal), but doffed it for this picture because of shadowing. The run took me six kilometers south of Bondi, to nearby Coogee Beach, along a truly majestic stretch of coastline. |

Well folks, that's all. See you back in the office!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed